RIVERHEAD, N.Y. — When Maureen Brainard-Barnes’ skeletal remains were found hidden in the roadside scrub near Long Island’s Gilgo Beach in the winter of 2010, there was hardly any physical evidence that might help investigators find her killer, save for a single stray hair.

But at the time, extracting DNA evidence from the degraded strand was beyond the capabilities of crime labs. Investigators kept looking for other clues that might help them identify a suspected serial killer who had scattered women’s bodies along a coastal parkway.

Then, about seven years ago, investigators turned to Astrea Forensics, a California lab using new techniques to analyze old, highly degraded DNA samples — including rootless hairs like the one discovered with Brainard-Barnes’ body.

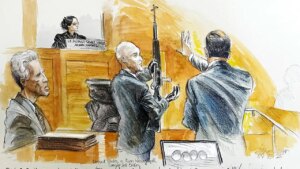

Now, that lab’s work is the focus of a pivotal decision in the closely watched case. A state judge is weighing whether to allow the DNA evidence generated through Astrea Forensics’ whole genome sequencing into the trial of Rex Heuermann, who is accused of killing 25-year-old Brainard-Barnes and six other women.

If allowed, it would mark the first time such techniques could be admitted in a New York court, and one of just a handful of such instances nationwide, according to prosecutors, defense lawyers and experts.

Prosecutors say Astrea’s findings, combined with other evidence, overwhelmingly implicate Heuermann, 61, as the killer.

But lawyers for the Manhattan architect argue the company’s calculations exaggerate the likelihood that the hairs recovered from the burial sites match their client.

“You can imagine the pressure that’s on this judge because he’s probably more than likely making a ruling that will set the stage for all the cases that come after,” said April Stonehouse, a DNA forensics expert at Arizona State University who is not involved in the case.

Advanced DNA analysis common in other scientific fields

DNA analysis is no longer new, but the tests typically used by criminal labs across the country have limitations.

Astrea is one of a small but growing number of private labs that say they are capable of taking extremely short DNA fragments found in very old bones and hair and using them to reconstruct a person’s entire genetic sequence, or genome.

During court testimony, experts called by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s office highlighted how scientists use similar techniques in a wide range of scientific and medical work, such as mapping the genome of the Neanderthal — an effort awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Astrea Forensics’ co-founder, Dr. Richard Green, described in court how his lab’s whole genome sequencing results were allowed as evidence in last year’s trial and conviction of David Allen Dalrymple in the cold-case murder of 9-year-old Daralyn Johnson in Idaho.

Defense suggests flaw in calculations

Heuermann’s lawyers argue that Astrea’s DNA methods haven’t been subjected to enough scrutiny yet, and warned they needed more evaluation because they had the potential to “dramatically reshape” how forensics is used in criminal trials.

They zeroed in on the statistical analysis Green’s lab conducted on the DNA profiles it generated from the hairs recovered from the victims’ remains, saying it was potentially overstating the likelihood that a mapped genome was a match with any particular person.

For its calculations, Astrea Forensics uses reference data from an open-source database containing the full DNA sequence of some 2,500 people worldwide, called the 1,000 Genomes Project.

Dr. Dan Krane, a professor at Wright State University in Ohio, testified for the defense that Astrea Forensics’ methods were “wildly and unfairly prejudicial.”

Prosecutors countered that Krane’s critique was “misguided” and revealed a “fundamental misunderstanding” of the lab’s methods.

Outside experts weigh in

William Thompson, a professor emeritus of criminology at the University of California, Irvine, who is not involved in the case, agreed with the defense that Astrea Forensics’ statistical analysis was “unvalidated” and lacked wide acceptance in the scientific community.

“This new technique may eventually be proven to live up to the claims of its promoters, but that hasn’t happened yet,” he said.

But Nathan Lents, a biology professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan, who is also not involved in the case, disagreed, suggesting the “mathematical quibble” didn’t warrant dismissing the evidence outright.

“The bottom line is that there are genuine scientific concerns with the way that the statistics are computed, but not with the laboratory techniques,” he said. “The concerns are real, but the likelihood ratios still look very damning for the defense, no matter how they are computed.”

Prosecutors have other evidence

Prosecutors have amassed other evidence against Heuermann, who is accused of killing women as early as 1993.

In court filings, they say cellphone call information and tracking data show that Heuermann arranged meetings with some of the victims shortly before their disappearances.

Last year, prosecutors revealed they had recovered from Heuermann’s computer files what they describe as a “blueprint” for the killings, including a series of checklists with reminders to limit noise, clean the bodies and destroy evidence.

They also have a second DNA analysis completed by a separate crime lab that used more traditional methods long accepted in New York courts. They say those findings, from Mitotyping Technologies, also convincingly link hairs found on some victims to either Heuermann or members of his family.

Investigators say that as he disposed of his victims, Heuermann used items from his house — including tape, belts, bags and a surgical drape — that had traces of hair from his wife and daughter.

In Brainard-Barnes’ case, though, only the advanced DNA tests performed by Astrea identified a match, finding the hair found with her remains belonged to Heuermann’s wife.

New York State Supreme Court Justice Timothy Mazzei is expected to announce whether he’ll allow Astrea’s DNA work into the trial during a Wednesday hearing in Riverhead.

Read the full article here